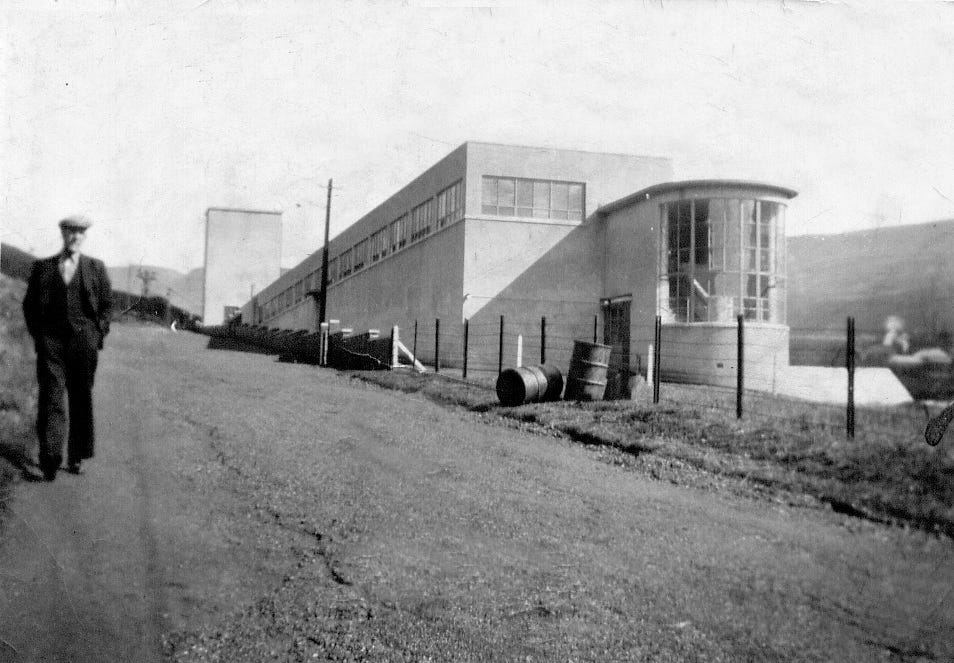

The Pithead Baths, Wyndham Colliery, Upper Ogmore Valley, South Wales, c.1928

As we approach the end of 2025, which also marks the end of the 40th anniversary year of the 1984–85 miners’ strike, this short essay reflects on my own experience of working as a miner. This reflection is particularly pertinent in light of the contemporary political climate in many former mining communities. Including their growing support for Nigel Farage and the Reform Party, and the latter’s romanticisation of working-class history as a central mechanism in its ideological appropriation of post-industrial communities.

The construction of pithead baths at collieries was a late arrival to industrial life in Britain. Until the 1920s, the idea that miners might wash before returning home was unusual, adopted only by the more progressive owners or financed through the Miners’ Welfare Fund, an institution to which miners themselves contributed, its resources reserved for welfare facilities or to assist in times of accident and unemployment. Only after nationalisation in 1947 did pithead baths become near-universal, a feature of the post-war social contract, signalling that dignity and physical welfare might, for once, take precedence over the single-minded pursuit of profit.

From their introduction in the 1920s until the last collieries closed in the 1990s, the sequence of activity surrounding the baths changed little. On the day-shift we would be due underground at 6:30, so would arrive perhaps forty-five minutes earlier. The act of changing into overalls was not part of the paid day. Entering through the ‘clean side,’ we would undress, placing clothes in a numbered locker. These lockers were double-decked, with a built-in bench that doubled as platform for reaching the top lockers; younger miners, like me, often found themselves allotted the higher compartment, climbing up to reach it. Clothes stored, we would—carrying soap, towel, and sandwiches—walk naked to the ‘dirty side,’ some in National Coal Board–issue flip-flops, others barefoot.

Here, amid the grit and coal fragments left over from the previous shift, soap was stowed, and NCB underwear donned: coarse grey vest and pants, followed by overalls—orange once, but generally faded to a pallid brown—consisting of shirt, jacket, and trousers. The lamp belt and boots followed and for coalface workers, like me, knee pads were strapped on before securing helmets. Sandwiches, wrapped in bread bags or stored in the rounded steel ‘snap tins’ unique to mining, were tucked into the shirt alongside the water bottle, often an old plastic cola bottle reused until failure. Some stopped to grease their boots against water ingress, though the younger men often skipped this step. From there, the short walk to the lamp room, to collect the cap lamp, self-rescuer respirator (for use in case of a methane gas explosion), and the brass ‘checks’ handed over before descent, marking one’s presence in the mine.

The end of a shift reversed the sequence. The ‘dirty side’ was always oppressively hot, the air drying the sodden overalls hung for the next day’s labour. Soap tray and flannel, often pub bar towels repurposed, were retrieved for the showers: rows of open-fronted cubicles, tiled in white, with black pitch floors. There was no privacy, and no need for it. Washing another man’s back was routine; flannels were exchanged without ceremony. For a face-worker, coal dust was implacable, embedded in the creases of the skin, especially around the eyes, where it produced a faint permanent darkness like mascara. Complete cleanliness was an illusion, perhaps attained briefly by Sunday evening, only to be undone the next morning.

The showers, especially on Fridays, were also a site of noise: jokes, horseplay, and, yes, song echoing from the tiles. Once washed, men returned to the ‘clean side,’ storing towel and flannel, dressing, and combing their hair before making for the canteen and a cup of tea.

This routine was neither sentimental nor symptomatic; it emerged not from romanticised notions of a mining “community,” but from a pragmatic need to endure the demands of the shift. A shared, if largely tacit, understanding of labour undertaken in hazardous and physically destructive conditions (and let’s not forget: all this in the name of the profit-margin) was offset by humour and camaraderie, which functioned as practical mechanisms for sustaining both morale and bodily endurance (and like any work situation, there was the presence of hierarchy, prejudice and coercion, too). In this sense, such practices carried a latent politics: not as overt resistance, but as everyday forms of negotiation and survival that shaped how power, risk, and vulnerability were collectively managed within the labour process. These everyday negotiations, in turn, informed a more generalised orientation toward politics (one that extended beyond the workplace and into activism; a framework to which I will return in a later essay).

The architecture of the baths, often bearing the stripped geometry of interwar deco or 1950s functionalism, embodied this collective reality. They were structures from a period in which there remained, however briefly, the conviction that resistance might be directed toward entrenched power rather than toward their designated scapegoats: the impoverished and the dispossessed.

Image credit: People’s Collection Wales.